This applies even to the brightest among us. We are phenomenal at dressing our monster-driven opinions as fact, thanks to our ability to confabulate.īut in reality, we’re simply characters in an issue of Modern Jackass (as Ira Glass illustrated in an aptly titled episode of This American Life, A Little Bit of Knowledge): people taking a tiny smidgen of understanding and stretching it far past the breaking point. And therefore, Celine Dion sucks her supporters are perpetuating the demise of the music industry and I am doing the world a favor by telling them so. It’s not because I’m “being emotional.” No, really: her music is objectively bad, she has no talent, she doesn’t write her own songs, she is a narcissist, blah blah blah. That lady doesn’t make my heart go on-her name almost induces cardiac arrest. There’s a good chance that at least one of these examples made your pulse speed up and your face warm for a split second. The urge to send a snarky tweet (or worse, to write a rude blog post) when the CEO of a Fortune 500 company redesigns its logo over the weekend.The instantaneous feeling of disdain toward a company that we loved, just after they announce they’re going to start making revenue from advertising.The anger directed at an “uneducated” colleague who just gave us negative feedback on a design concept.Maybe these examples will hit closer to home? The propensity to fire off a hasty and nasty response to an email perceived as rude.The urge to chase down someone who cuts us off on the freeway.The need to put down someone’s taste in music because they confess they like Celine Dion.

And you can definitely see the amygdala’s propensity for fight or flight in these examples, if you squint just right: Like protecting our delicate egos.īut evolution doesn’t happen overnight.

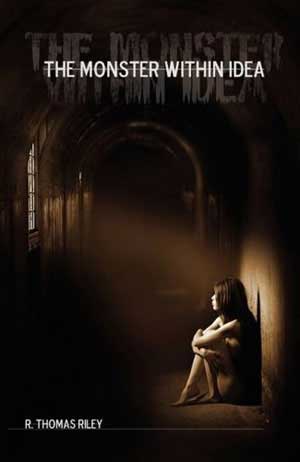

Instead of being on the lookout for predators or incoming spears from rivals, the amygdala spends all its time on relatively more trivial matters. And as a result, there’s a diminished need for the amygdala’s role as bodyguard. In the amygdala’s world, the only thing between life and sudden death is a few measly milliseconds.īut in our #firstworldproblems, we rarely encounter life-or-death situations. (Biggie is referring to squeezing the trigger, of course.) And for good reason. If the amygdala were to get a tattoo across its chest, it’d be Notorious B.I.G.’s “Squeeze first ask questions last,” in Gothic Olde English. And to that end, it has evolved to save our lives by making split-second decisions with not only very little data at hand, but without the participation of a conscious mind. The amygdala’s top functional focus is to keep us alive at all costs. The amygdala, one of the earliest to evolve parts of the brain, is responsible for the fight or flight instinct: that reflexive, subconscious reaction that protects us in moments of dire danger. It’s because I believe that even a high-level understanding of this curious part of our brains can dramatically improve each of our lives. It’s no accident that I referred to the amygdala in my first and second pieces. This is because there is a monster within us, and it’s called the amygdala 1. “Give me short-term gratification, or I will make your life miserable!” is the brain’s modus operandi as it communicates with itself to help us live our lives. It also happens to be a frighteningly good metaphor for how our brains work. I recently learned that the phrase “trick or treat” is short for “Give me a treat or I will play a trick on you.” It’s actually a threat. Brief books for people who make websites.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)